CONTENT

Introducing

DECEMBER 2025

peace flies on dove’s wings in quiet minds peace sings

In her poem The Wild Geese Mary Oliver gives us this context for her birds,Meanwhile the world goes on. Meanwhile the sun and the clear pebbles of the rain are moving across the landscapes, over the prairies and the deep trees, the mountains and the rivers. Meanwhile the wild geese, high in the clean blue air, are heading home again. Whoever you are, no matter how lonely, the world offers itself to your imagination, calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting— over and over announcing your place in the family of things.

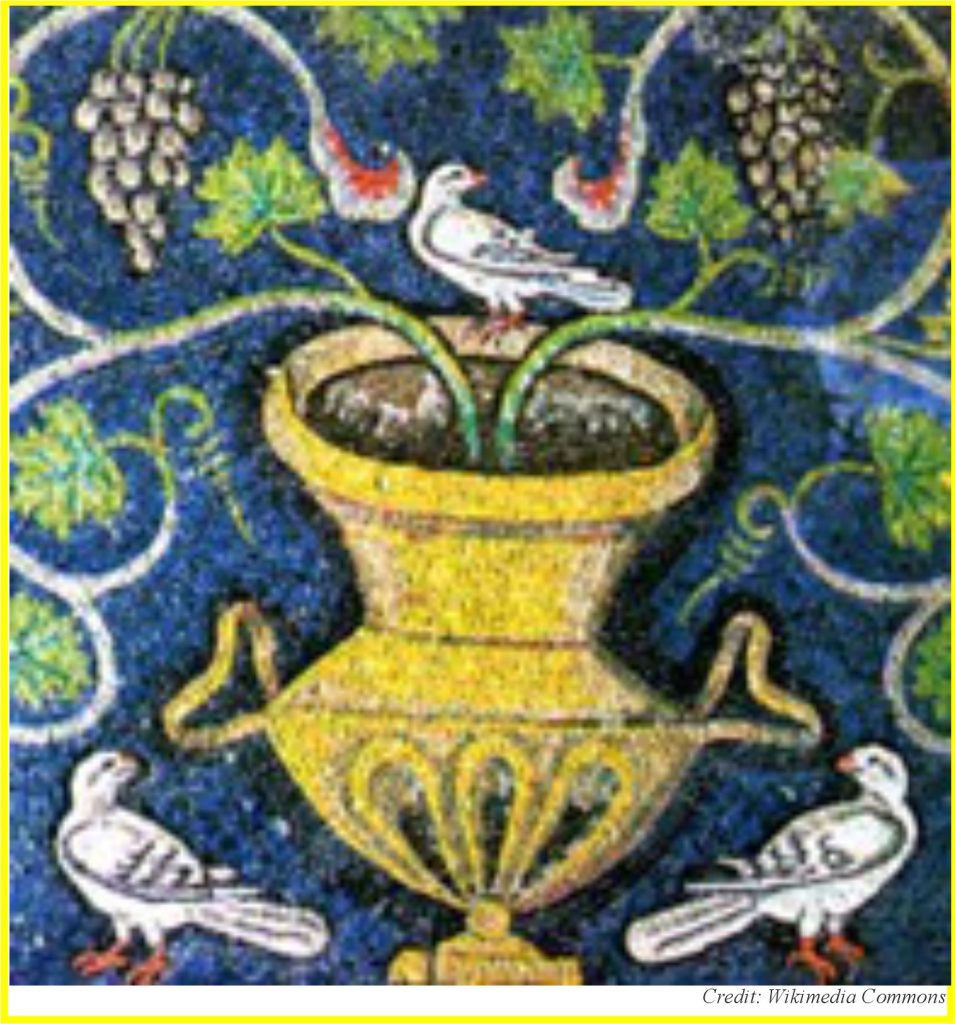

The dove: Noah’s dove returning with an olive leaf, the dove of the Holy Spirit descending, or perhaps Picasso’s dove, created in 1949 for the first International Congress of Peace; the snow goose; and then there’s the crested crane of the African savannah, Uganda’s national bird, its elegant form a harbinger of peace in many other African countries. We seek with such wild creatures to symbolize the peace we crave. As Wendell Berry writes,When despair grows in me…. I go and lie down where the wood drake rests in his beauty on the water, and the great heron feeds. I come into the peace of wild things

When we look at fauna, we choose to name the pure white lily our flower of peace. This month’s STS, – the last issue overall of these blogs, since the year ends with the month of December reached – has taken PEACE as its theme. ‘Peace on earth, goodwill to all men’, the angels sing above the Nativity crib at Bethlehem. In a song about the Virgin Mary Caritas abundat in omnia (Love abounds in everything) Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1178) wrote, ‘To the highest King the kiss of peace she gave.’ The song can be found on her album, Kiss of Peace. Bingen was a German abbess of phenomenal intellect and outreach, a mystic and visionary, prolifically composing sacred music, writing both music and words. Listen to the clip below to hear how a soprano voice soars in its purity and, mantra-like in their repetition, Bingen’s lyrics soothe and upliftART OF THE MONTH

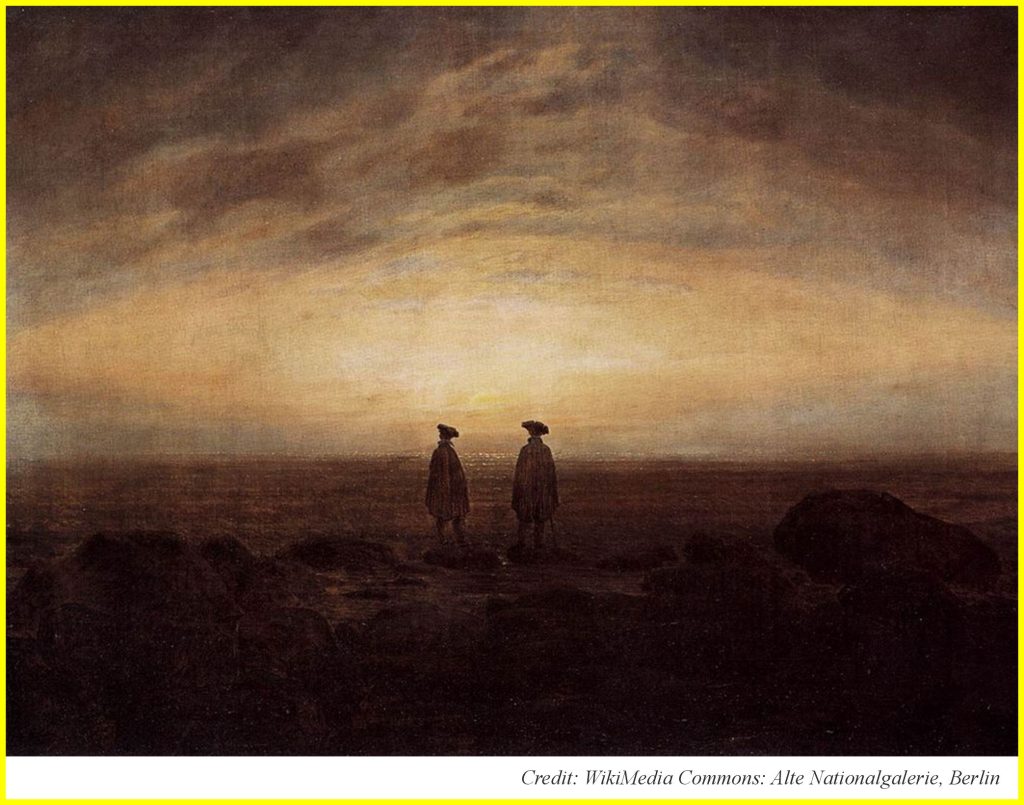

TWO MEN BY THE SEA AT MOONRISE

by

CASPAR DAVID FRIEDRICH

1774 -1830

In the calendar:

Not specifically a religious painting, there is no calendar date to which this work is connected. Caspar David Friedrich (CDF) favoured dawn and dusk as the timeframes for many of his compositions. In this one we see a clouded sky in which a veiled moon rises over a flat expanse of water that’s been described as ‘moonstruck.’ The two men are well wrapped up and the work’s palette: ochre, shades of grey, brown and the black rocks of the beach suggest it as a winter scene.

The frame of reference:

CDF came of age at a time when Europe was turning from materialism, with a new appreciation of spirituality being expressed by artists such as J M W Turner. At art school he was taught that nature was a revelation of God. CDF was to develop a distinctly Romantic approach to landscape painting, focussing on the effects of light, as for example how the sun and moon illuminated water. Two Men by the Sea was painted in 1817, a year which was one of severe suffering for Germany, failed harvests and food shortages having resulted from the atmospheric disruption of a massive southern hemisphere volcano. It is suggested the light pollution experienced over a period of months is reflected in the pinkish palette used by CDF, which was perhaps a way for him to render elements of his vision of the apocalypse.

The painting:

The canvas is a small one: 51 x 66 cms. It has been described as ‘a quintessentially spiritual Romantic painting,’ one which beckons the viewer to join the two standing, back-turned and silhouetted figures ‘in a wordless but deep emotional encounter with nature.’ They stand, their expressions closed to us, but evidently rapt in contemplation of the mystery and grandeur of an empty landscape, where an occluded moon rises above an expanse of darkly ominous sea.

The painting evokes the Romantic ideology of nature as a reflection of the soul – but lays itself open to interpretation as so much of CDF’s work does. The moon, not simply illuminating the landscape may suggest yearning, eternity, and the sublime, its ascension perhaps symbolizing the progress from life to death, or the striving of the soul upwards to the infinite.

Our gaze is invited into the painting by this barely-seen moon, which nevertheless is blurring the line between heaven, sea and shore. Do we empathise with the tranquillity of the scene which the two men have discovered, and do we conclude they are at peace, experiencing the brightening sky being ushered in by the moon as its blessing? Or are we more convinced that the mood of the work is intended as sombre, bleak. And that this portends the painting’s overarching message as despairing, the artist having transformed the shy moon into a metaphor of human failing, of the need for attention to be urgently directed to spiritual perception and metaphysical reflection?

The artist:

CDF’s story is one of extremes: a man who came from a lonely and tragic childhood to achieve great fame and the highest success and be considered the most important German artist of his generation, only to fall out of fashion and favour and die almost destitute. CDF’s talent was recognised early. Settling in Dresden in 1798 at the age of 24, he began to paint northern landscapes in what was seen as a new and challenging way, sketching on the spot and then working on his finely-tuned depictions of the effects of changing light, the sun and the moon. In 1808 his most renowned painting of The Cross in the Mountains, an austere portrayal of a cross set up high profiled against a great sky, startled his audiences, who asked whether landscape artistry belonged in religious settings. Elected a Member of the Berlin Academy in 1810 after the Crown Prince bought two of his paintings, CDF ran into political difficulties and began to distance himself from the mainstream art world. After marrying in 1818 his palette became brighter and lighter but as he aged, he fell further out of the public view. Isolated, he became a solitary and was ill for the years leading up to his death in 1840.

CDF’s often melancholy and isolationist view of the world linked with the strongly religious undertones of his work has always invited controversy. After a long period of neglect, last year, 2024, there was a series of major exhibitions in Hamburg, Berlin, Dresden and New York and Weimar to mark the 250th year of his birth

LITERATURE

THE SNOW GOOSE

by

PAUL GALLICO

1897-1976

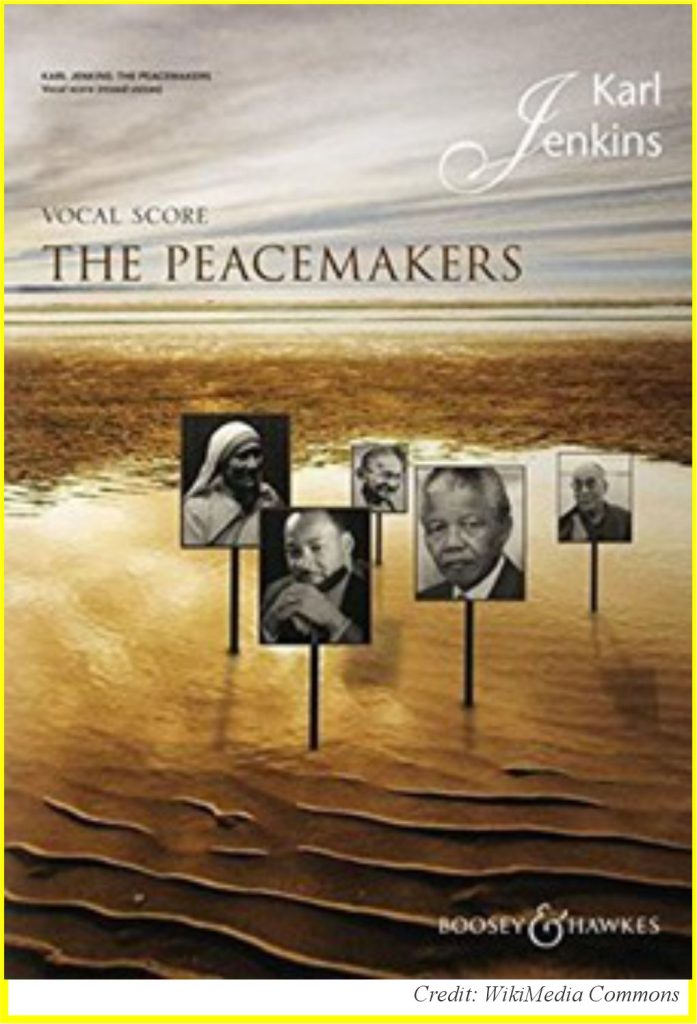

KARL JENKINS AND THE PEACEMAKERS –

uplifting words set to soul-stirring choral music

‘All religions, all singing one song: Peace be with you’, a line from a poem by the C13th Persian mystic poet Rumi, sums up the composition’s overarching ethos of universality and collaboration.

Jenkins writes, ‘When I composed an earlier Mass, The Armed Man: A Mass for Peace for the Millennium, it was with the hope of looking forward to a century of peace. Sadly,’ he reflects, ‘more than a decade later nothing much has changed.’

This newer take, Jenkins’ sequel, is nevertheless a strong extolling of peace, in which he has transmitted his composition’s message through the words of an eclectic selection of individuals whose thinking across the ages about the importance of peace to humankind has remained inspirational.

Many of those whose words are heard on The Peacemakers are iconic figures whose speeches have shaped history and made their mark on the world in situations of conflict and/or rapid change.

We know of these figures through their political action, their humanitarian involvements, their writings. Some of the text comes from lesser known but nevertheless salient individuals with significant contributions to make.

Included are:

Percy Bysshe Shelley, Mahatma Gandhi, The Dalai Lama, Terry Waite, Mother Teresa, Albert Schweitzer, St. Francis of Assisi, Sir Thomas Malory, Rumi, President Nelson Mandela, Bahá’u’lláh.

Jenkins explains how he has placed some of the texts he selected from the speeches within a musical context embellished in such a way that it helps identify and enrich their origin, as for example:

- the bansuri (Indian flute) and tabla used for Mahatma Gandhi’s contribution.

- the shakuhachi (a Japanese flute associated with Zen Buddhism) and temple bells, in that of the Dalai Lama.

- African percussion in the tribute to President Nelson Mandela

- echoes of the blues of the deep American South as well as a quote from Schumann’s ‘Dreaming’ for what’s heard from Martin Luther King

- uilleann pipes and bodhrán drums in the ‘Healing Light: a Celtic prayer’

The Abrahamic religions are brought into the piece with the words of Jesus Christ; from the Qur’an; from Judaism; and from Russian Orthodoxy in the words of monk Saint Seraphim of Sarov; while Saint Francis of Assisi is included by association.

There are words from the Old Testament Book of Isaiah, representing a homage to the oratory of Martin Luther King, who drew on the prophet Isaiah for his own prophetic 1963 ‘I have a dream’ speech given at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington DC, USA.

Words from poets who span four centuries of English verse, Sir Thomas Malory from the C14th and Percy Bysshe Shelley of the C19th, are also heard, as is the voice of Iranian religious leader, Bahá’u’lláh (1817-1892), the founder of the Bahá’í faith.

Jenkins notes that from our more contemporary period he has included quotations from the diary of Anne Frank, and that human rights activist Terry Waite CBE (b 1939) has contributed ‘some wonderful words.’

In harnessing words’ transformative power in this way, uplifting them into song, Jenkins has assured that any performance of The Peacemakers can, in itself, be seen as an act of defiance, unleashing its veritable onslaught of words directed with all the strength it can muster towards celebrating the cause of peace

A Madonna casts her blessing on the waters of the Venetian lagoon from the southernmost

extremity of the garden on Giudecca restored by the Venice Gardens Foundation at the

Redentore, the Church of the Most Holy Redeemer

STOP WAR - say ‘Peace’ in all languages!

The slogan above belongs to the campaign initiated by the Internet Internationalization (I18N) community, an organization which values diversity and human life everywhere.

In its manifesto I18N states,

‘The people of the world prefer peace to war – and they deserve to have it. Bombs are not needed to solve international problems when they can be solved just as well with respect and communication.’

As our farewell in this last NOTES&JOTTINGS we offer you the greeting ‘Peace.’

In a random medley of the world’s languages, one small word – readying itself to be one first small step towards better international understanding, more successful mediation.

- SOUTH AFRICA (Afrikaans) – vrede

- ALASKA – kinuinak

- ALGERIA – lahna

- AZERBAIJAN – sul

- CONGO (Bangi) – nyiEe

- CORNWALL – cres

- CORSICA – pace

- CZECH – mir

- DENMARK – fred

- EAST AFRICA (Kiswahili) – amani

- EGYPT – salam

- ESPERANTO – paco

- FIJI – vakacegu

- GERMANY (Middle High) – vride

- HAWAII – maluhia

- ITALY – pace

- INDIA (Hindi) – shanti

- ISRAEL – shalom

- KENYA (Kikuyu) – thayu

- KOREA NORTH and SOUTH – pyeonghwa

- LITHUANIA – taika

- MADAGASCAR (Malagasy) – fandriampahalemana

- AMERICA (Sioux) – wo’ okeyeh

- NORWAY – fred

- PAPUA NEW GUINEA – taim billongska

- PHILIPINNES (Tagalog) – kapayapaan

- POLAND – pokoj

- RUSSIA – mir

- SENEGAL (Mandinka) – kayiroo

- SPAIN – paz

- SUDAN – salam

- TURKEY – baris

- UKRAINE – spokiy

- WALES – tangnefedd

- WEST AFRICA (Wolof) – jamm